Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$cat_ID is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 357

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$category_count is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 358

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$category_description is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 359

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$cat_name is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 360

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$category_nicename is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 361

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$category_parent is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 362

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Post::$post_category is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/class-wp-post.php on line 266

R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots) is ascience fiction play written by the Czech writer Karel Čapek which is the source of the word Robot. The play imagines synthetic people called roboti (robots) who are created to work for humans but eventually rebel which leads to the extenction of humans. R.U.R was translated from the Czech language … Continue reading RUR in Ottoman Turkish]]>

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Post::$post_category is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/class-wp-post.php on line 266

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Post::$post_category is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/class-wp-post.php on line 266

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Post::$post_category is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/class-wp-post.php on line 266

The book is available for download at the web archive.

]]>Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Post::$post_category is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/class-wp-post.php on line 266

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Post::$post_category is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/class-wp-post.php on line 266

http://www.islamscifi.com/rur-in-ottoman-empire/feed/

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$cat_ID is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 357

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$category_count is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 358

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$category_description is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 359

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$cat_name is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 360

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$category_nicename is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 361

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$category_parent is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 362

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$cat_ID is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 357

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$category_count is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 358

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$category_description is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 359

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$cat_name is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 360

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$category_nicename is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 361

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$category_parent is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 362

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$cat_ID is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 357

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$category_count is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 358

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$category_description is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 359

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$cat_name is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 360

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$category_nicename is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 361

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$category_parent is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 362

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Post::$post_category is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/class-wp-post.php on line 266

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Post::$post_category is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/class-wp-post.php on line 266

Turkish Science Fiction has come a long way and it will not be long before Turkey produces world class sci-fi. Long before Sadik Yemni, GORA, Book of Madness etc there was Dünyayı Kurtaran Adam or The Man Who Saved the World. It was one of those movies which are so bad that they are good. … Continue reading Dünyayı Kurtaran Adam (The Man Who Saved the World)]]>

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Post::$post_category is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/class-wp-post.php on line 266

Turkish Science Fiction has come a long way and it will not be long before Turkey produces world class sci-fi. Long before Sadik Yemni, GORA, Book of Madness etc there was Dünyayı Kurtaran Adam or The Man Who Saved the World. It was one of those movies which are so bad that they are good. The movie is famous for its over the top premise and using unauthorized footage from Star Wars as well as the US and the Soviet space program. The premise is that Murat and Ali are friends who crash land on a planet. While trekking across a desert on the planet they speculate that the planet is inhabited only by women! It is not clear how they came up with that premise but lets grant them this premise for now. One of them uses his special whistle to attract women (yes there is such a thing in this movie) but instead of women they get skeletons on horses. Later on we run into 1,000 year wizards from Earth, Zombies, golden ninjas, space swords, golden human brains etc. The film was universally panned by critics in Turkey but understandably this movie has gained a cult following.

]]>Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Post::$post_category is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/class-wp-post.php on line 266

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Post::$post_category is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/class-wp-post.php on line 266

http://www.islamscifi.com/dunyayi-kurtaran-adam/feed/

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$cat_ID is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 357

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$category_count is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 358

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$category_description is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 359

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$cat_name is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 360

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$category_nicename is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 361

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$category_parent is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 362

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Post::$post_category is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/class-wp-post.php on line 266

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Post::$post_category is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/class-wp-post.php on line 266

Sadik Yemni is a Turkish-Dutch novelist who has been called the Lord of Turkish Fiction. His work combines multiple genres like detective fiction, science fiction, drama, paranormal, horror and humor. Here is a synopsis of some of his well known science fiction novels: The Other Side (Öte Yer): A probe launch to the moon in … Continue reading Sadik Yemni]]>

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Post::$post_category is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/class-wp-post.php on line 266

Sadik Yemni is a Turkish-Dutch novelist who has been called the Lord of Turkish Fiction. His work combines multiple genres like detective fiction, science fiction, drama, paranormal, horror and humor. Here is a synopsis of some of his well known science fiction novels:

The Other Side (Öte Yer): A probe launch to the moon in the mid-sixties sends back the message “Is every thing O.K. D-Boy?” years after it has been terminated. The message appears to be authentic but everyone is puzzled about the message since the probe was silent for such a long time.

Solvent (Çözücü): In 2004, in the middle of Takim square in Istanbul 50,000 people disappear without a trace and for no apparent reason. Only 26 people survive in a small region with an invisible barrier around them which no one can cross. No one is sure what is going on: Simulated reality? Mind-over-matter? Alien abduction? False memory?

Metros: A few thousand years ago a bright light appears in the sky in Istanbul and turns people into mutants. While many of them are killed by the locals but some of them survive to the present day.

Immortal (Ölümsüz): Immortal is described as a sufi science fiction. Ayhan Timir is working in a hotel where he is fired after only a few months. Soon afterwards he receives a mysterious photograph with himself in it in an envelope and 1,400 liras in his bank account from a non-existent source. He keeps on receiving these two items every month until he receives a different picture and he realizes that he has to eliminate the person in the image. He also discovers that none of his previous acquaintances seem to recognize him.

]]>Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Post::$post_category is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/class-wp-post.php on line 266

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Post::$post_category is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/class-wp-post.php on line 266

http://www.islamscifi.com/sadikyemni/feed/

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$cat_ID is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 357

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$category_count is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 358

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$category_description is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 359

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$cat_name is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 360

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$category_nicename is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 361

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$category_parent is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 362

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$cat_ID is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 357

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$category_count is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 358

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$category_description is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 359

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$cat_name is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 360

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$category_nicename is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 361

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$category_parent is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 362

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Post::$post_category is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/class-wp-post.php on line 266

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Post::$post_category is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/class-wp-post.php on line 266

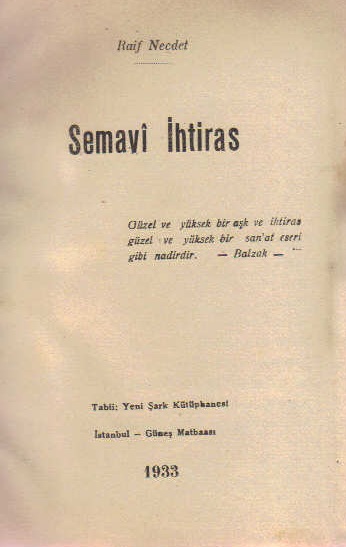

One of the earliest Turkish Sci-Fi Utopias was written by the Turkish nationalist author Raif Necdet. In Semavi İhtiras (The Celestial Passion), published in 1933 a future secular and republican Turkish utopia is imagined. The story is about Nobel-prize winning Turkish authors and Turkish girls who have many more freedoms including freedom of mobility as … Continue reading Naif Necdet Semavi İhtiras]]>

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Post::$post_category is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/class-wp-post.php on line 266

One of the earliest Turkish Sci-Fi Utopias was written by the Turkish nationalist author Raif Necdet. In Semavi İhtiras (The Celestial Passion), published in 1933 a future secular and republican Turkish utopia is imagined. The story is about Nobel-prize winning Turkish authors and Turkish girls who have many more freedoms including freedom of mobility as compared to the contemporary milieu, not just in Turkey but in the rest of the world as, in which Necdet was writing about e.g., the girls in the novel have private jets which they use to fly over the world.

]]>Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Post::$post_category is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/class-wp-post.php on line 266

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Post::$post_category is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/class-wp-post.php on line 266

http://www.islamscifi.com/naif-necdet-semavi-ihtiras/feed/

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$cat_ID is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 357

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$category_count is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 358

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$category_description is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 359

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$cat_name is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 360

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$category_nicename is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 361

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$category_parent is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 362

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Post::$post_category is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/class-wp-post.php on line 266

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Post::$post_category is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/class-wp-post.php on line 266

Baska Dunyalar Mumkun or Other Worlds Are Possible is a compilation of science-fiction reviews and critiques. It is the first literary anthology of its kind in Turkey devoted to the subject of Science Fiction as a literary genre – the anthology of science-fiction, dystopia and cyberpunk to be exact. The publishing of this volume also … Continue reading Baska Dunyalar Mumkun (Other Worlds Are Possible)]]>

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Post::$post_category is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/class-wp-post.php on line 266

Baska Dunyalar Mumkun or Other Worlds Are Possible is a compilation of science-fiction reviews and critiques. It is the first literary anthology of its kind in Turkey devoted to the subject of Science Fiction as a literary genre – the anthology of science-fiction, dystopia and cyberpunk to be exact. The publishing of this volume also demonstrates the arrival of Science Fiction as a literary genre in Turkey, although it still has a long way to go. The volume deals with the themes in the works of Frank Herbert, Issac Asimov, Philip K. Dick etc. It was described as the best book of the year 2007 by the Turkish Literary Review Magazine.

[Thanks to Murat E. for the info]

]]>Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Post::$post_category is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/class-wp-post.php on line 266

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Post::$post_category is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/class-wp-post.php on line 266

http://www.islamscifi.com/baska-dunyalar-mumkun-other-worlds-are-possible/feed/

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$cat_ID is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 357

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$category_count is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 358

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$category_description is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 359

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$cat_name is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 360

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$category_nicename is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 361

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$category_parent is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 362

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Post::$post_category is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/class-wp-post.php on line 266

Science Fiction and Fantasy in Turkey seems to be reaching a critical mass. Not only is Turkey producing more Science Fiction but the quality of Science Fiction coming from Turkey has improved significantly. Thus it would be most appropriate to start the series of Turkish Science Fiction with FABİSAD (Fantasy and Science Fiction Arts Association) … Continue reading Science Fiction and Fantasy Collective in Turkey]]>

Science Fiction and Fantasy in Turkey seems to be reaching a critical mass. Not only is Turkey producing more Science Fiction but the quality of Science Fiction coming from Turkey has improved significantly. Thus it would be most appropriate to start the series of Turkish Science Fiction with FABİSAD (Fantasy and Science Fiction Arts Association) which is a newly created organization dedicated to the promotion of fantasy, science fiction and horror. The organization plans to have science fiction awards for Turkish Sci-Fi as well regular meetings, seminars, book drives and workshops in this area. Here is an excerpt from TimeOut with FASIBAD regarding the history of speculative fiction in Turkish:

MÜSTECAPLIOĞLU: If you go back to very old times, Turkey was a land of shamanism, which resembles high fantasy in some ways. There was an oral culture back then, and some storytellers would make fantastic illustrations to accompany their stories. My latest book is about a 13th-century storyteller, Mehmet Siyahkalem, who drew incredible illustrations of demons with snake-headed tails and other fantastical creatures to accompany his stories. A little later, there’s the epic of Dede Korkut. But when the Ottomans came and found shamanism here, they wanted to establish a new religious culture, so they tried to destroy the shamanistic roots. And after that, the republic was established. The republicans wanted to change Turkey’s religious culture into a more secularist culture, so they cut all study of fairy tales and other imaginative things from schools. Everything imaginative was hushed up.

SOYAK: Imagination became something that people began to ignore or fear. They began to spread the message that Turkey needed more factory workers than dreamers: “Don’t think, just work.” There are lots of sayings in Turkish that discourage you from being imaginative or creative. I’m not saying it’s only a bad thing — in fact, the main point of the sayings is just, “Be careful, don’t get lost in your dreams.” But there are so many of these sayings that it’s actually a little alarming.

MÜSTECAPLIOĞLU: They wanted to block all imaginative traditions and make people believe only in science and things that they can prove. There were still some artists and writers in the early republican period who ignored this, and continued producing imaginative work. But they were told that their work was childish, and that they must only write about the real Anatolia. Nobody asked the government to define reality, or why its idea of reality should be everyone else’s reality. They ignored the fact that people with strong imaginations can create a better life for themselves than the government’s so-called reality.

YÜCEL: They didn’t only ignore imaginative works, they ignored experimental novels too. Anything that wasn’t mainstream. Oğuz Atay, for instance, is now considered one of the most important Turkish writers. But he wasn’t successful in his own time, because at that time people found his novels too personal, too out of the social reality.

On the FABISAD logo:

]]>The inspirer of the FABİSAD logo is the legend of Simorgh Phoenix and Qaf Mountain. This legend summarizes the establishment philosophy of FABİSAD as well.

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Post::$post_category is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/class-wp-post.php on line 266

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Post::$post_category is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/class-wp-post.php on line 266

http://www.islamscifi.com/science-fiction-and-fantasy-collective-in-turkey/feed/

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$cat_ID is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 357

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$category_count is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 358

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$category_description is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 359

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$cat_name is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 360

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$category_nicename is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 361

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Term::$category_parent is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/category.php on line 362

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Post::$post_category is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/class-wp-post.php on line 266

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Post::$post_category is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/class-wp-post.php on line 266

[Image Source: Murat Palta’s Artwork] Starting today and until next Friday I will be doing a series of daily posts on Turkish Science Fiction. This will include serious works of science fiction to not so series science fiction cult movies from Turkey from the 1980s. As Turkey’s profile has risen in the world so has … Continue reading Turkish Science Fiction Week at Islam and SciFi!]]>

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Post::$post_category is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/class-wp-post.php on line 266

[Image Source: Murat Palta’s Artwork]

Starting today and until next Friday I will be doing a series of daily posts on Turkish Science Fiction. This will include serious works of science fiction to not so series science fiction cult movies from Turkey from the 1980s. As Turkey’s profile has risen in the world so has the quality of Science Fiction in the world. Also I would like to acknowledge my Turkish friends and acquaintances for introducing me to the world of Turkish sci-fi and for most of the references for the posts for the next 7 days. The posts will range from serious and critically acclaimed Science Fiction by Levent Şenyürek, to Murat Palta’s miniatures, to goofy Space Balls like Sci-Fi Comedy to the classic rip-off comical movies like Dünyayı Kurtaran Adam. This also illustrates that Turkish sci-fi has come a long way in the span of 3 decades. Book like Baska Dunyalar Mumkun have acclaim in the wider literary community in Turkey as well. Bariș Müstecaplioğlu’s Land of Berg also deserves a special mention.

]]>Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Post::$post_category is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/class-wp-post.php on line 266

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property WP_Post::$post_category is deprecated in /homepages/15/d218977245/htdocs/wp-includes/class-wp-post.php on line 266

http://www.islamscifi.com/turkish-science-fiction-week-at-islam-and-scifi/feed/